Opportunity NOx – What Next for Diesel?

This year Barker Brettell’s automotive team headed up by Dr Andy Tranter, patent attorney and partner, will be publishing a series of articles that highlight innovative developments in mechanical engineering. Today, Andy along with trainee patent attorney Calum Bradbury, turn their attention to diesel engines.

“Coughs and sneezles spread diseasals”, quipped Bill and Ben the tank engines when they first encountered Diesel. Coming from two coal-fired steam engines, this is probably a bit of a pot and kettle situation, but diesel’s reputation as a dirty fuel is often cited as a reason to buy petrol-powered vehicles. However, diesel engine technology has come a long way since its inception, so what technologies have created this improvement and can future technologies secure diesel’s place in the market?

The Past

Rudolph Diesel’s new internal combustion engine for burning ‘fuel of any kind’ emerged in 1892 with US patent 542,846 – a patent for an entirely new product; a rare occurrence these days. The innovation provided greater efficiency than the process of known spark-ignition engines, despite some early models being powered by peanut oil. Initially capturing the market in large marine engines, diesels found their way into the production car market with the Citroën Rosalie in 1933.

Although acknowledged as being more efficient in terms of fuel consumption, and thus generating lower carbon dioxide and carbon monoxide emissions, early diesel engines, often accompanied by a cloud of smoke, were renowned for generating pollution of their very own – particulates and NOx. Trying to rectify its dirty image, manufacturers sought to find ways of cleaning up these emissions.

The Present

Diesel particulate filters (DPFs) and exhaust gas recirculation (EGR) were introduced to road vehicles in the 1970s and 1980s in an attempt to reduce soot and harmful NOx emissions, which were far higher than those of petrol engines due to the higher compression ratios and temperatures of operation.

Further efforts to reduce NOx as it became more of a buzzword in the 2000s led to the introduction of selective catalytic conversion (SCR) that reduces NOx by the introduction of ammonia – mainly in the form of AdBlue® – to the exhaust gases, emitting only nitrogen gas and water. SCR surfaced in cars in the 2000s, and remains a popular technology for improving NOx emissions in diesels, with each marque trying to build up an associated brand. Mercedes’ BlueTEC®, BMW’s BluePerformance®, and Citroën and Peugeot’s BlueHDi are each being pushed as the answer to the diesel emission problem.

Alternatively, NOx traps use molecular sieves to trap the NOx prior to removal by modifying engine operation for a short period, thus avoiding the downsides of EGR. All these advances have made diesel engines much cleaner, pushed by the recent introduction of Euro 6 emission standards. Engines abiding by these standards, such as the most recent Mercedes BlueTEC® systems, surely go some way to silence diesel’s critics.

The Future

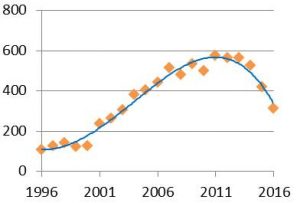

So what next? As shown by the graphic below, patent publications relating to clean diesel emissions have fallen sharply since 2011, indicating that the industry had been looking to alternative fuels and technologies even before the latest spate of bad-press, and is well-placed to deal with market forces. With changes to public policy and emphasis on green technology, innovation has been directed more towards hybrid and electric vehicles rather than cleaning up the emissions of diesel engines. However, with 99% of commercial vehicles in the UK being diesel-powered along with 52.5% of the new car market (based on sales in March 2017), there is clearly still room for innovation.

As an example, improvements from F1 are starting to find their way into production, where supercapacitors of KERS (kinetic energy recovery system) fame are being used to assist turbochargers in an attempt to generate more power and lower emissions at low engine speeds.

Government funding available for green technology has accelerated the progress of some technology. The Advanced Propulsion Centre (APC) has recently provided £62m to various initiatives to help the UK become a global leader in low emissions technology. Successfully-funded projects include collaborations led by Williams Advanced Engineering, Jaguar Land Rover, and Penso Consulting, developing high performance batteries, lightweight vehicles, and composite structure manufacturing, respectively. Although these latest projects are yet to come to market, they are a clear indication of the intention of companies to continue to innovate.

As can be seen, although diesel-emission specific patent filings might be dropping, there is still room for innovation in the sector. Furthermore, the push to hybrid and zero-emission vehicles continues to provide many more opportunities for development.

Automotive technology remains a key part of the work of Barker Brettell in each of patents, trade marks, and designs. If you would like to discuss your automotive innovation, please contact Andy Tranter, head of the automotive sector, or your usual Barker Brettell attorney.